A College’s “Admit Rate” Doesn’t Mean What You Think

Those of us with an interest in the college admissions process, applicants and their families, college admission professionals on both sides of the desk, and the vast industry that these participants support, are complicit in the perpetuation of a dreadfully unhealthy paradigm.

“Admit Rate” has become synonymous with quality. This is highly unfortunate, since the correlation is tenuous, at best, and the statistic itself is easily susceptible to manipulation. We reward colleges for low admit rates and then allow the numbers to intimidate us.

Two decades ago, one college rep said to me “Sadly, a college is considered ‘good’ if it disappoints many of the kids who apply to it.” So, by extension, a college is considered “superior” if it disappoints nearly all who apply. Following that logic, then, wouldn’t the “best” college simply admit no one?

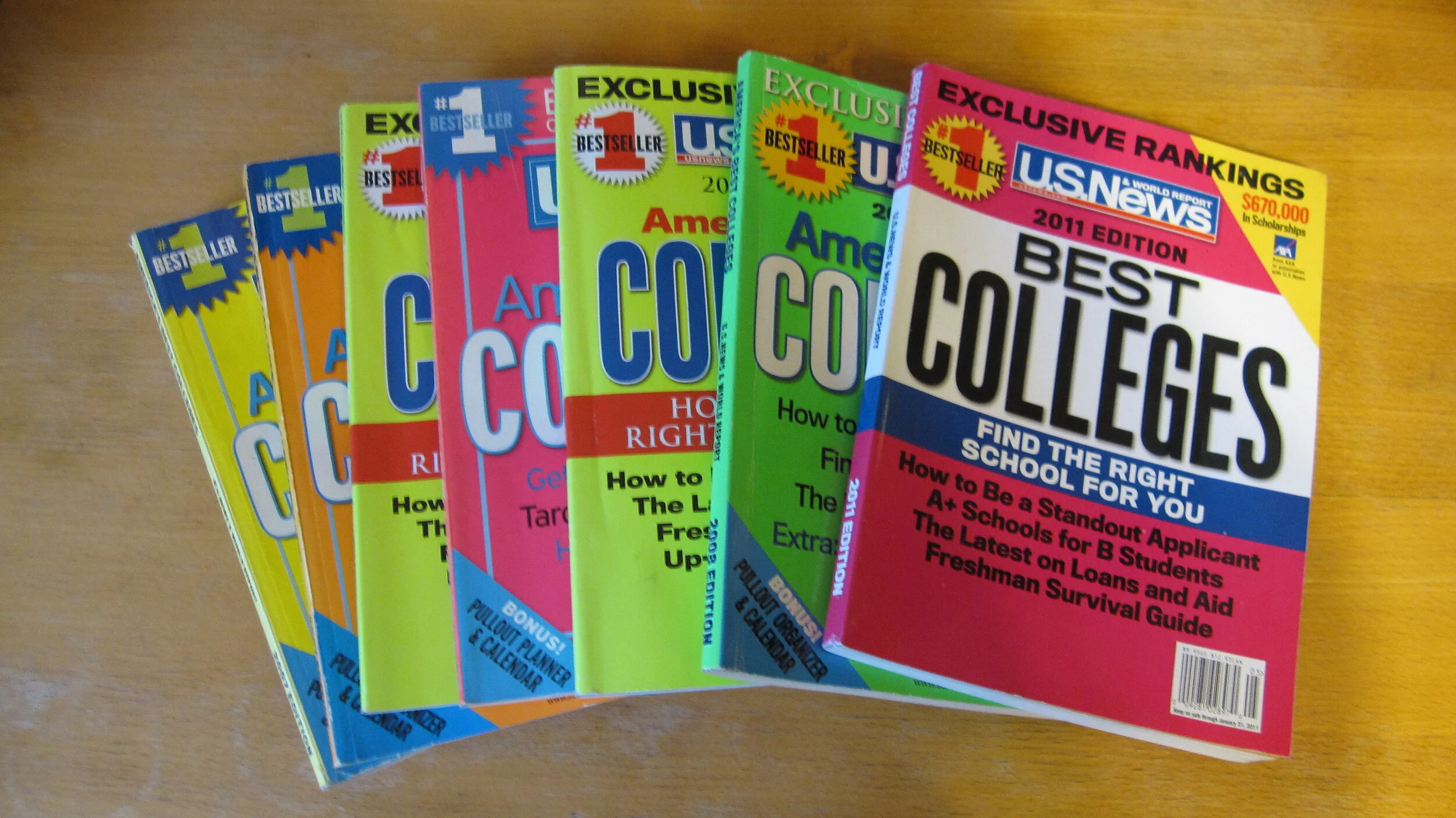

It really started with US News and World Report. A reliance on “admit rate” and “yield” as cornerstones of their rankings methodology fueled a frenetic process that has engulfed us. We have not only sipped the “Admit Rate” Kool Aid, we have filled the Croton Harmon reservoir with it. It is the epitome of irony to me that US News and World Report, a highly respected business magazine, ceased publication in December 2010, yet its annual college rankings issue continues to flourish.

I rarely ask boys to rank order their college lists, since it is usually an exercise that leaves me frustrated and forlorn. Invariably, the boy’s list shows a nearly perfect correlation with the admit rates of the schools on the list. I get it. Boys (and their parents) routinely announce: “I just want to go to the best school I can get into.” But the sole criterion seems to be selectivity—someone else’s “best.” Looked at from only a slightly different perspective, the applicant is saying that the only “good” schools are ones that will not admit him.

The best way to evaluate a school would be to spend a semester there as a full-time matriculated student. That’s unrealistic, however, so the trick is to figure out what characteristics matter to you. Rankings are an easy solution, but by their very nature they encourage applicants to leave themselves out of the equation and focus solely on quantifiable factors that are only loosely associated with the undergraduate experience.

In my College Prep classes and my College Night presentations, I do a quick math review on admit rate. It’s a simple quotient: number of students admitted divided by number who applied. In order to lower the admit rate, you need to admit fewer kids or get more to apply. The former leads to a revenue shortfall. The latter is the way to go.

Suppose we are the admissions office at a small, perfectly nice liberal arts college somewhere in rural America. We have 500 seats in the freshman class and we typically receive 2,000 applications. We admit 1,500 of those students in order to fill the class, since two of every three will choose another offer. That gives us an admit rate of 75% and a yield of 33%. Our faculty like the kids we bring in and the model appears sustainable.

Our Board of Trustees, however, feels that we should appear more competitive and has instructed us to lower the admit rate. Our simplest strategy would be to contact the College Board and/or ACT and order the names and email addresses of, say, 10,000 students, at 47¢ apiece. We send those kids an email congratulating them on their academic achievement and inviting them to apply to our fine school. We tell them how much we love them and how much we are looking forward to enrolling them. We waive the application fee and the essay; all they have to do is click the link.

Understand that we don’t need these kids; we don’t even have to like them; they don’t need to be good, or even satisfactory, candidates. All we need them to do is click. If we can get 1,000 of them to do that, then we have 3,000 applications. We admit the same 1,500 we would have, but now our admit rate is 50%. We have become more competitive and, therefore, “better” by changing nothing about our school.

Two years ago, the Dean of Admission at a top research university told me they would be cutting back on high school visits and re-directing the travel budget to buy more names from the College Board. This really happens because it really works.

Suppose instead, we start a round of binding early decision (ED). If we can get 500 of those kids to apply ED and we take 250 of them, then we only need to admit 750 in the regular pool to fill the class. Once again, our admit rate has dropped to 50% (1,000/2,000), but in this scenario, our “yield” has also risen from 33% to 50%.

Selective colleges and universities have been increasing the number of seats they fill with ED and that pace accelerated this year. (More on this in the next blog!) Using only one offer of admission to fill a space keeps their precious admit rate as low as possible while simultaneously locking in qualified candidates. Filling 50% of a class early is now de rigeur, and a number of selective schools came in closer to 75% this year. That invariably forces the regular decision admit rate to plummet, which, of course, is precisely the point.